Pablo Picasso, a name that evokes the essence of modern art, remains one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. His prodigious output spans various mediums, including painting, sculpture, printmaking, and ceramics, leaving an indelible mark on the art world. Born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, Spain, Picasso transformed the art landscape with his innovative approaches, pioneering Cubism and engaging with numerous other art movements throughout his long career.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Picasso’s artistic journey began in the vibrant cultural settings of late 19th-century Spain. His father, José Ruiz Blasco, an art teacher and painter, recognized early on his son’s exceptional talent and nurtured it diligently. By the age of seven, Picasso had begun formal artistic training under his father’s guidance, mastering traditional techniques with an astounding precocity.

In 1895, the family moved to Barcelona, a city that played a critical role in his development as an artist. Barcelona’s bustling artistic community and its modernista influences profoundly impacted the young Picasso. His admission to the prestigious La Llotja school further honed his skills, and soon, his works were displayed in various exhibitions. During this period, his style began to show signs of the innovative spirit that would define his later work.

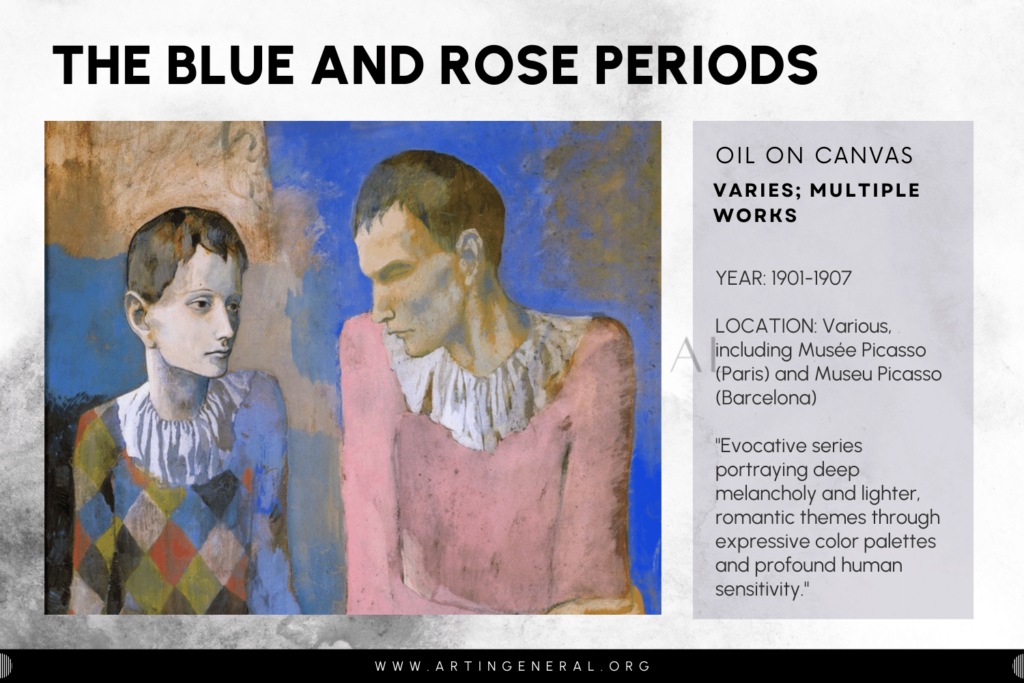

The Blue and Rose Periods

The Blue Period (1901-1904) marked one of Picasso’s first major thematic and stylistic shifts. Triggered in part by the suicide of his close friend Carlos Casagemas, this period was characterized by somber monochromatic paintings in shades of blue and blue-green, underlined by a profound sense of human misery and desolation. Works such as “The Old Guitarist” and “La Vie” showcase his interest in depicting the suffering of the impoverished, the ill, and the outcasts of society. The figures in these paintings are often elongated, their forms twisted in expressions of despair.

Transitioning from the emotional depth of the Blue Period, The Rose Period (1904-1906) exhibited a lighter palette and a turn toward more cheerful subjects such as circus performers, acrobats, and harlequins. These characters from the world of the itinerant circus lent a sense of romanticism and escape, reflecting Picasso’s improved circumstances and his integration into the vibrant cultural life of Paris, where he had moved in 1904. Notable works from this period include “Family of Saltimbanques” and “Boy with a Pipe,” which exhibit a significant departure from the melancholy of the Blue Period through warmer colors and a more optimistic perspective.

Invention of Cubism

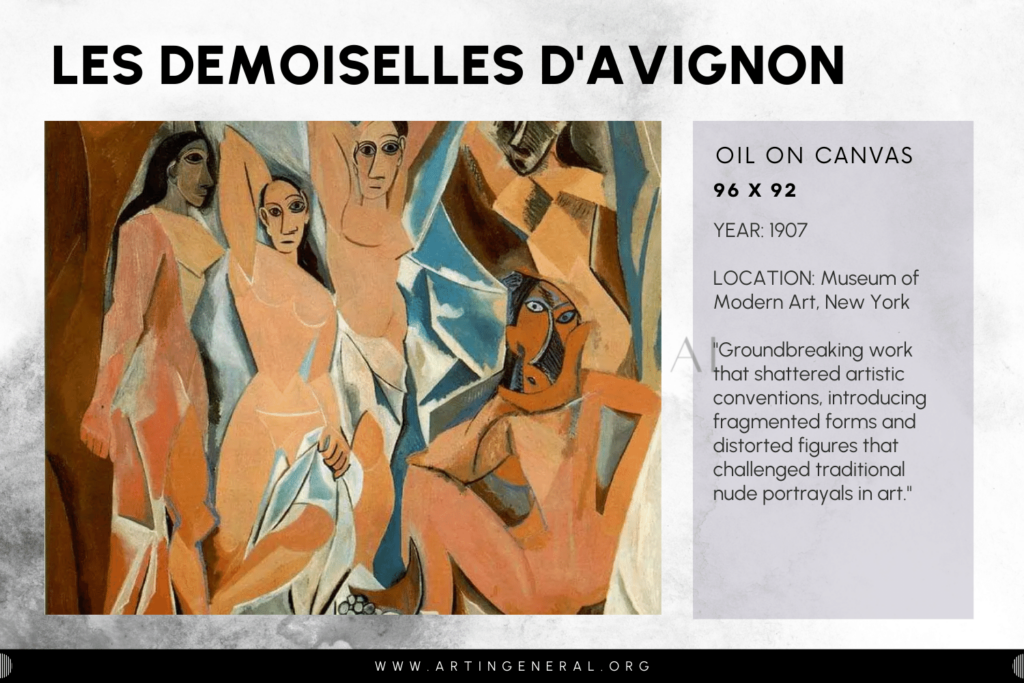

Picasso’s move to Paris introduced him to a milieu that was at the forefront of modern art. Here, his artistic sensibilities underwent another profound transformation leading to the invention of Cubism. The seeds for this revolutionary art form were planted with the creation of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” in 1907. This painting broke away from traditional perspectives, presenting a radical depiction of five disfigured prostitutes with bodies composed of geometric shapes and disjointed spaces.

This artwork marked a dramatic shift in artistic representation and was instrumental in the development of Cubism, a movement co-founded with French artist Georges Braque. Together, they began to deconstruct the conventional forms of perspective and representation in art. Analytic Cubism, the first phase of the movement, saw Picasso and Braque analyzing and breaking down objects into fragmented components and muted color palettes, as seen in works like “Ma Jolie.”

Evolution of Cubism

After laying the groundwork with “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Picasso, alongside Georges Braque, continued to push the boundaries of traditional art forms. Analytic Cubism, characterized by fragmented surfaces and subdued colors, was the first phase in this evolution. Both artists focused on breaking down objects into basic geometric forms and reassembling them on the canvas, creating a new sense of depth and multiple perspectives within a single artwork. This period is best exemplified by works such as “Portrait of Ambroise Vollard” and “Girl with a Mandolin.”

Following Analytic Cubism, Picasso and Braque developed Synthetic Cubism, which introduced brighter colors and mixed media into their works. This phase marked the introduction of collage art, using non-traditional materials such as newspapers and rope, which further blurred the distinctions between painted surfaces and real-world textures. This innovative approach is evident in Picasso’s “Still Life with Chair Caning,” where he used oilcloth with a chair-cane design and rope as a frame, merging real objects with painted ones to challenge the viewer’s perception of reality.

Major Artworks and Series

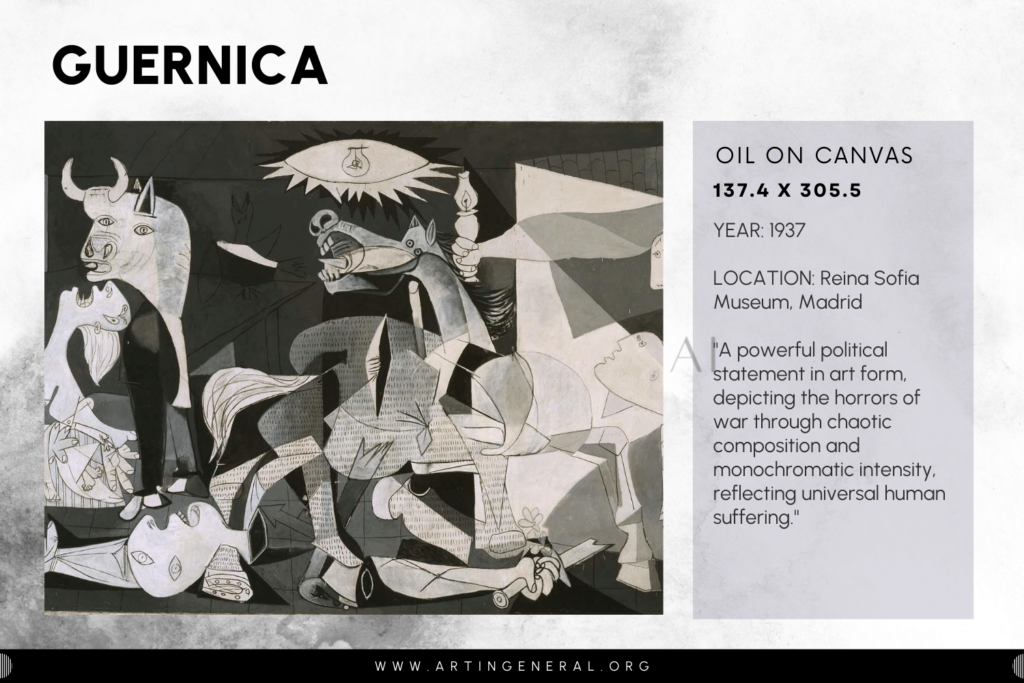

Among Picasso’s expansive oeuvre, several series stand out for their influence and artistic brilliance. “Guernica” (1937), perhaps Picasso’s most famous work, is a poignant political statement against the brutality of the Spanish Civil War. This monumental black and white canvas embodies the chaos and suffering of war and has become an enduring symbol of anti-war sentiment. It showcases Picasso’s mastery of a narrative style that remains impactful and relevant.

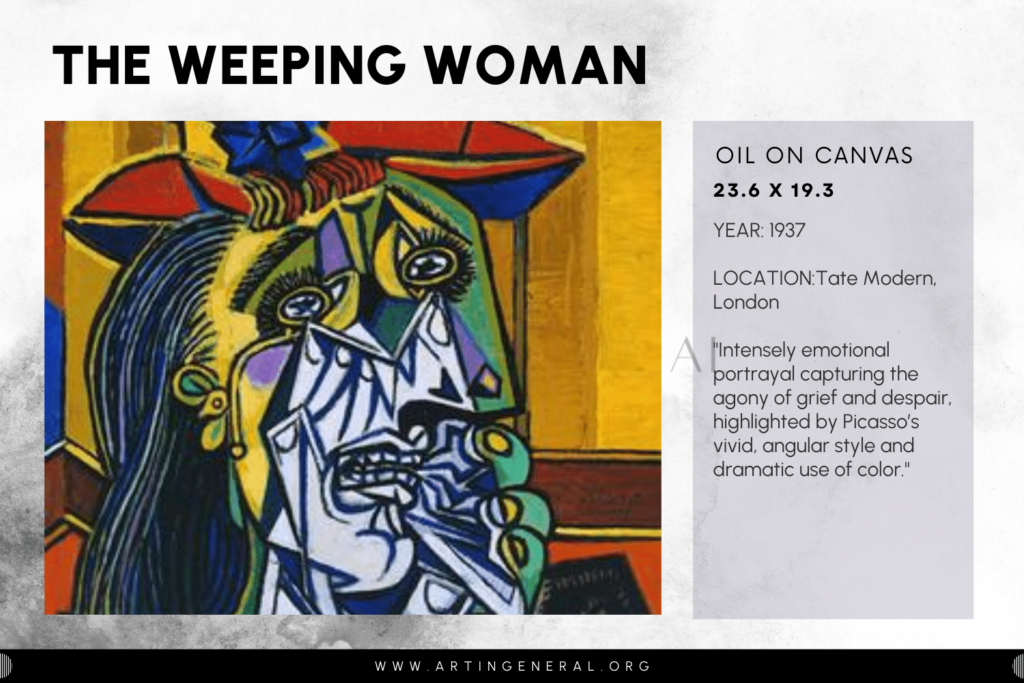

His “Weeping Woman” series is another significant work, through which Picasso explored themes of suffering and tragedy, representing universal sorrow in the aftermath of war. Each piece in this series portrays a woman in distress, her features distorted in a style reminiscent of his Cubist influences, vividly expressing the emotional turmoil of the time.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective in painting. It depicts five nude prostitutes in a brothel, but the depiction is far from realistic. The figures are rendered in a stark, angular manner, with distorted bodies and masked faces inspired by African and Iberian art. This painting is considered revolutionary for its introduction of Cubist elements and its departure from European painting norms, effectively setting the stage for the development of modern art. The disjointed planes and fragmented geometry challenge the viewer’s perception of depth and perspective, making it a cornerstone of Cubist expression.

Guernica (1937)

Created in response to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, this large mural-sized oil painting is one of Picasso’s most famous works and a poignant political statement against war. Rendered in a monochromatic scale, “Guernica” uses a chaotic composition featuring dismembered body parts, a gored horse, a bull, and distressed female figures to evoke a sense of frenzied pain and suffering. The painting is devoid of color to perhaps reflect the somber reality of destruction and death. “Guernica” is lauded not only for its bold statement but also for its impactful use of Cubist techniques to communicate a powerful narrative.

The Weeping Woman (1937)

“The Weeping Woman” is part of a series that Picasso created as a continuous exploration of suffering. The subject, Dora Maar, Picasso’s lover and a prominent photographer, is depicted with a highly expressive composition that reflects grief and agony. The use of sharp geometric fragmentation in her face and the saturated colors enhance the emotional intensity of the painting. This work is often viewed as an extension of the tragedy depicted in “Guernica” and is a profound commentary on personal and collective pain.

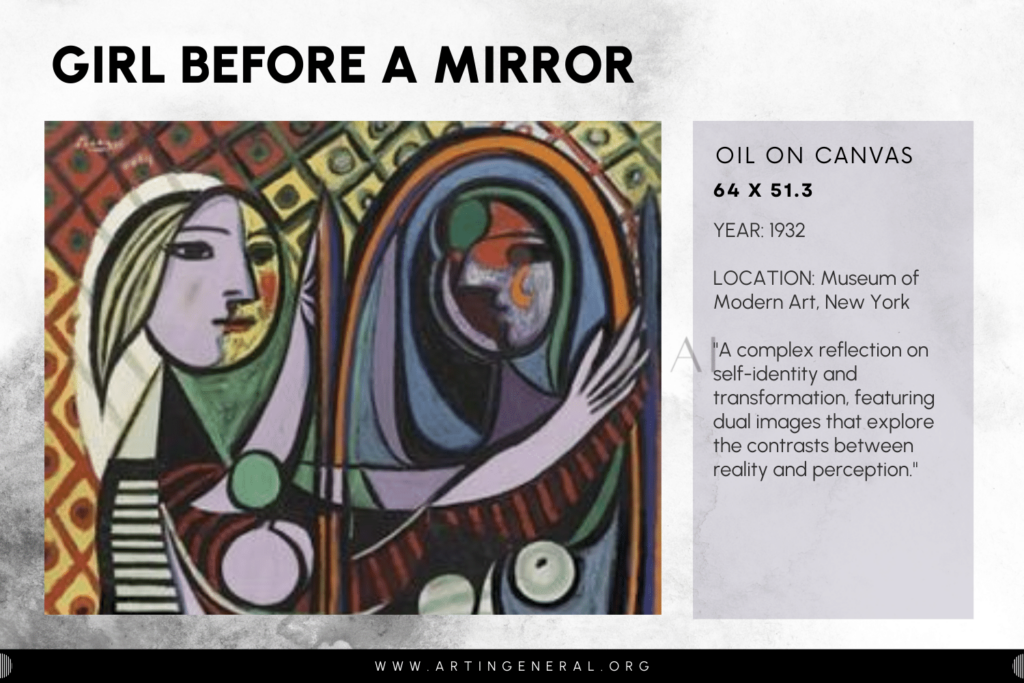

Girl Before a Mirror (1932)

This painting, part of Picasso’s series on his young mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, shows her confronting her reflection in a mirror. The composition splits into two halves: the real figure and her reflection. Symbolically rich, the painting explores themes of vanity, duality, and the complexities of feminine identity. The contrast between the vibrant, colorful depiction of the girl and the darker, more distorted reflection suggests a complex interplay of light and shadow, youth and old age, and beauty and inner turmoil. The reflective surface distorts and abstracts the figure, a typical Cubist manipulation by Picasso that invites viewers to question the relationship between reality and perception.

Personal Life and Inspirations

Picasso’s personal life was as vibrant and complex as his art. His relationships with women not only influenced his artistic style but often directly inspired his works. For instance, the Rose Period was influenced by his warm relationship with Fernande Olivier, while the emotional depth of the Blue Period has been attributed to his despair over the death of his friend Casagemas and his own struggles during his early years in Paris.

His later muse, Dora Maar, was a significant figure during the 1930s and inspired many portraits, including elements of the “Weeping Woman” series. Picasso’s shifting relationships are often mirrored in the changing themes and styles of his artwork, reflecting his personal experiences and the emotions they evoked.

Moreover, Picasso was deeply influenced by political events, most notably during the Spanish Civil War. His political engagements are vividly reflected in “Guernica,” showcasing his ability to channel his political outrage into his art, making powerful socio-political statements.

Picasso’s Global Impact

Pablo Picasso’s impact on the art world was monumental and continues to echo across continents and cultures. As a pioneer of modern art, he influenced countless artists and inspired numerous art movements. His introduction of Cubism radically shifted the direction of contemporary art by challenging traditional forms and perspectives, thus paving the way for future abstract art.

His work not only influenced his immediate contemporaries but also shaped the practices of future generations of artists around the globe. Picasso’s ability to amalgamate different styles and mediums has inspired artists to experiment and innovate in their own art, thereby fostering creativity across various disciplines including sculpture, ceramics, and graphic arts. His global impact is also seen in how his art has been integrated into cultural education, helping to define the visual language of modernism for scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Picasso and Cultural Institutions

Picasso’s relationship with cultural institutions began early in his career and evolved significantly over time. Today, major museums around the world, such as the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, the Musée Picasso in Paris, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, hold extensive collections of his works. These institutions not only preserve his vast oeuvre but also organize retrospectives that explore his diverse artistic phases.

His influence extends into the academic realm, where his innovative techniques and distinctive style are studied extensively. Educational programs focusing on his art-making process, thematic exploration, and historical context provide insight into his creative genius, influencing new generations of artists and art historians.

Preserving Picasso’s Legacy

Efforts to preserve and promote Picasso’s legacy are multifaceted, involving meticulous conservation, authentication, and exhibition of his art. The Picasso Administration oversees his estate, managing copyrights and working against forgery. Moreover, advances in digital technology have allowed for the creation of extensive archives, making his work more accessible to the public and helping to maintain his influence in the digital age.

Educational initiatives and collaborations with various institutions ensure that Picasso’s contributions to art continue to be appreciated and studied. These efforts also help to sustain his relevance in the art world, ensuring that his work remains vibrant and significant.

Picasso in Popular Culture

Picasso’s influence extends well beyond art galleries and academic discussions; he permeates popular culture, symbolizing creativity and the quintessential image of the modern artist. His life and works have been the subject of films, literature, and media, often portraying him as a complex figure intertwined with the romantic notion of the tortured artist.

His distinct style and iconic persona are frequently referenced in advertising, design, and media, showcasing his lasting impact on contemporary culture. Picasso’s art and image continue to inspire, challenge, and provoke, cementing his status as a cultural icon.

Leave a Reply